Natural Gas and the Environment

Introduction

As a source of energy, natural gas releases far fewer pollutants and greenhouse gases than either oil or coal. Most natural gas recovery in the USA, until recently, has been from natural, underground reservoirs, using processes similar in many ways to those used in the extraction of oil. Indeed, many reservoirs tapped for oil contain natural gas.

However, recent development of processes for economical extraction of natural gas from shale formations have increased public concern about the environmental effect of those processes. Those concerns include the overuse and contamination of water tables, land misuse, threat to endangered species and other environmental problems.

Additionally, methane, of which natural gas is almost entirely composed, is a gas with a greenhouse warming effect several times that of carbon dioxide. Leakage of methane into the atmosphere is a potential problem in its impact on the global climate and must be carefully monitored in any natural gas extraction process.

There is an additional dark side to natural gas, and that is to be found, strangely, in one of the coldest, most isolated spots on the earth, the Arctic region, including the Arctic Ocean and the bays and land areas surrounding it. Therein lie massive amounts of methane hydrates, either in permafrost or sequestered in submerged, frozen organic matter, which, upon thawing, releases methane, potentially in prodigious quantities. Methane is a highly potent greenhouse gas, much more so than carbon dioxide, and the warming taking place in those Arctic regions threatens to release methane in quantities that could threaten the climate of the earth in ways that are both rapid and extensive.

Methane Hydrates

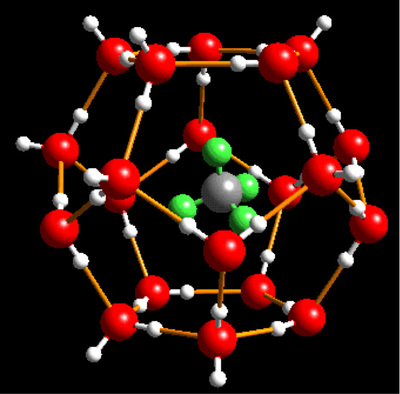

Methane Hydrate

(water: red and white; methane: silver and green)

source: USGS

A methane hydrate is a type of clathrate, which is a molecular lattice containing an entrapped compound. In the case of a methane hydrate, the clathrate is a lattice "cage" formed of water molecules (H2O), within which is trapped one or more methane (CH4) molecules.

In order to preserve the hydrate structural stability, the temperature and pressure must be at levels that maintain the system in an ice form. Methane hydrates have been found in the permafrost of such land areas as Siberia and Alaska, where the year-round temperature does not rise above 0° Celsius. In ocean environments methane hydrates are extensive in sediments at shallow depths, not exceeding 2000 meters below the surface. In all cases the temperature is sufficiently low to maintain the ice structure year round. Methane hydrates have also been found in fresh water lakes in polar regions of Siberia.